Astronomers now recognize 88 constellations. A memory aid I’ve used through the years is that there are the same number of constellations as keys on a full piano keyboard. Today’s star groups cover the sky with no overlaps and no gaps between them. This, however, is a fairly recent development.

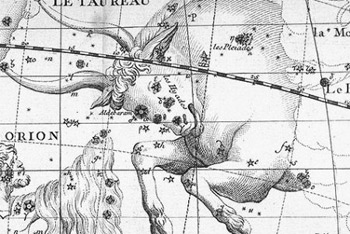

Before 1928, celestial mapmakers were free to populate the skies as they pleased, with only the mildest restraint placed upon them by astronomers and other cartographers. The fact that many of the star groups in use at the turn of the 20th century no longer exist compels me to refer to the Darwinian axiom of survival of the fittest.

Before 1928, celestial mapmakers were free to populate the skies as they pleased, with only the mildest restraint placed upon them by astronomers and other cartographers. The fact that many of the star groups in use at the turn of the 20th century no longer exist compels me to refer to the Darwinian axiom of survival of the fittest.

The first star maps and celestial globes had fewer than 50 constellations. Despite that relatively small number, some of those 50 have not survived. The most notable example is the massive constellation Argo Navis, named after the legendary ship that carried Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece. Argo Navis is the only star group that fell into disuse for purely practical reasons: It was simply too big.

So, in the middle of the 18th century, astronomers subdivided Argo Navis into the constellations Carina the Keel, Puppis the Deck, and Vela the Sails. This change made it much easier to catalog objects in the three new constellations.

So ingrained was the use of the star designations in Argo Navis that, when the new constellations appeared, astronomers retained the original set of Greek letters and added no new ones. So, Puppis and Vela have no Alpha star. Argo Navis’ single Alpha star — Canopus — now resides in Carina.

Every other constellation that has gone the way of Argo Navis has vanished because the international community of astronomers has not accepted it. Many of these star groups honored the mapmaker’s patron or his country’s monarch. Those living outside the boundaries of the relevant country didn’t always accept these tributes. A similar row ensued when English astronomer Sir William Herschel tried to name his newly discovered planet Georgium Sidus, or “George’s Star,” after the King of England. That didn’t fly, especially in France, so we call the solar system’s seventh planet Uranus.

Astronomers finally agreed to the number of constellations and their boundaries in 1928. Six years earlier, at the inaugural meeting of the International Astronomical Union (IAU), organizers had instructed a subcommittee led by Belgian astronomer Eugene Delporte to formalize them, thus eliminating any discrepancies from future star maps. Delporte reported to the IAU in 1928 and, in 1930, the official publication Délimitation Scientifique des Constellations appeared. All star maps published following this decision conform to the subcommittee’s definitions.

As somewhat of a constellation historian, I’ve researched many of the extinct constellations. Trust me, we’re not missing much at all. “Survival of the fittest” once again proved its merit. Now, I’m off to play the piano.